Translated By Tony Qin

In Chan (Zen) practice, deeply contemplating certain phrases from koans is known as “investigating the critical phrase.”

The term koan originally referred to legal cases or precedents in the courts of the Tang dynasty. In the Chan tradition, the words and actions of great masters across generations were carefully recorded and transmitted as guidance for spiritual practice. Over time, these recorded dialogues became objects of meditative inquiry and touchstones for insight. Because these records were considered to awaken wisdom—and were regarded with the same authoritative weight as legal precedents—they came to be known as koans.

The koan tradition began during the Tang dynasty and flourished in the Song dynasty. While there are approximately 1,700 recorded koans, only about 500 are commonly studied today. These koans are preserved in key Chan classics such as The Blue Cliff Record, The Gateless Gate, The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, The Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp, The Record of Pointing at the Moon, and The Five Lamps Meeting at the Source.

What is the content of a koan? Take, for example, the koan known as “Not a Single Word Spoken.” Before entering parinirvana, the Buddha was asked by Manjushri Bodhisattva to seize that final moment to teach the Dharma once more. The Buddha replied, “Manjushri, for forty-nine years I have taught in this world, yet I have never spoken a single word. Now you ask me to speak again—have I ever spoken the Dharma? I have never spoken a single word, nor have I ever spoken the Dharma.”

In terms of ultimate reality, the nature of Dharma cannot be conveyed through words or language. Spoken teachings are like a finger pointing to the moon—they show the direction so that one may see the moon, but the finger itself is not the moon. This koan illustrates that from the moment the Buddha turned the Dharma wheel until his final silence, all his teachings were merely the pointing finger. The phrase “not a single word spoken” expresses that the fundamental nature of the Dharma is beyond the bounds of language.

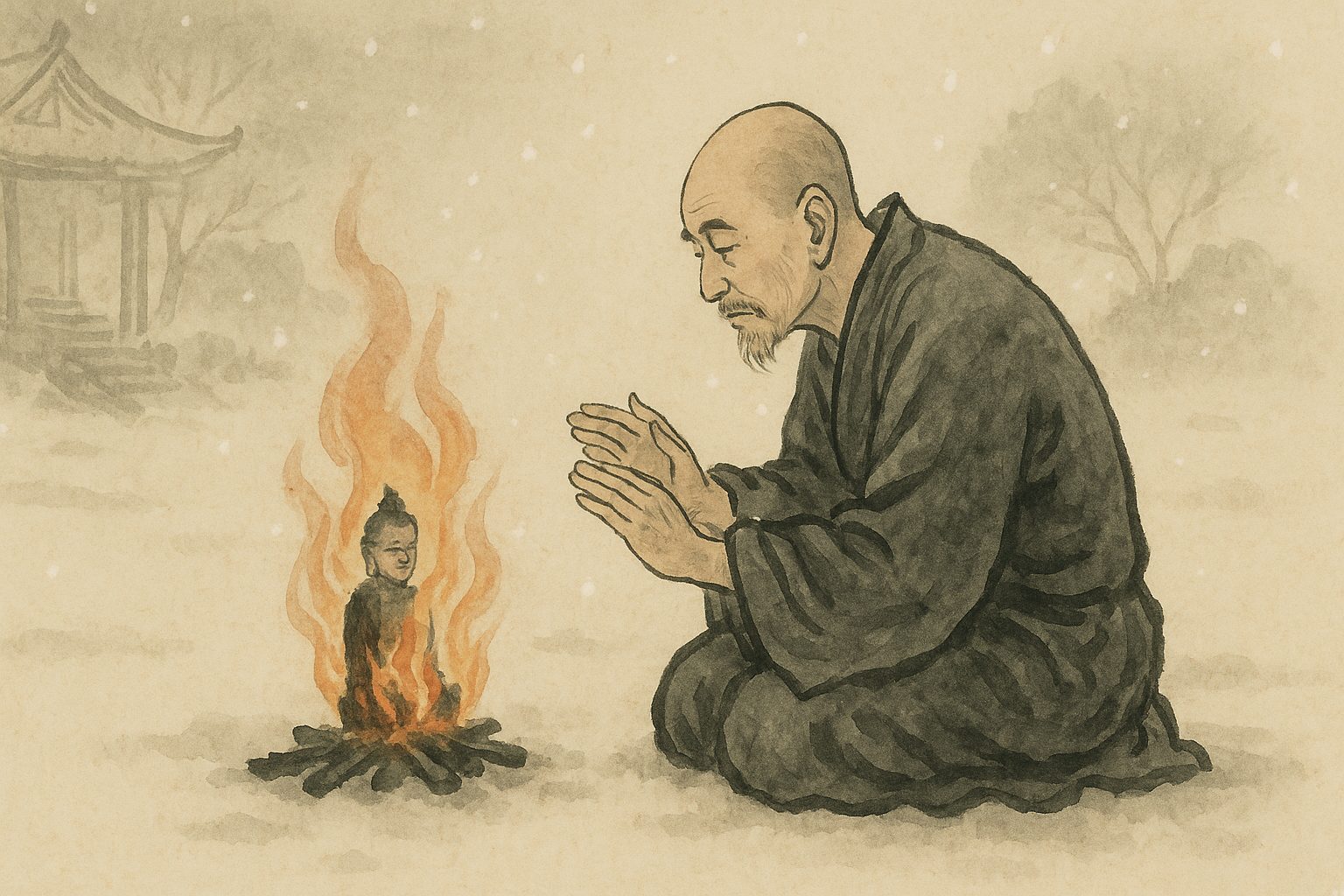

Another well-known koan is “Danxia Burns the Buddha.” During his stay at Huilin Temple, Chan Master Danxia was faced with extremely cold weather. In an unexpected act, he took a wooden Buddha statue and burned it for warmth. The other monks were outraged and accused him of grave disrespect. In response, Danxia said, “You misunderstand! I am not disrespecting the Buddha. I’m cremating it to produce śarīra pearls.”

The monks retorted, “How could a block of wood produce śarīra pearls?”

Danxia answered, “If you already know that a Buddha statue is just a block of wood, then why accuse me of disrespect for burning it for warmth?

This koan challenges the common misunderstanding of taking physical objects to be the Buddha himself. When Danxia burned the statue, he was making a point—he wanted to break people’s attachment to external images made of wood or clay. We need to recognize that bowing to and making offerings in front of Buddha statues are symbolic gestures—they’re outward forms of practice. The true Buddha is found within our own minds, in our innate nature. We shouldn’t confuse a statue with the living presence of the Buddha. Rituals alone aren’t enough. Real devotion means living out the Buddha’s qualities—his wisdom, compassion, and conduct. Only by letting go of our afflictions and attachments can we truly awaken to our own Buddha-nature. Venerating the Buddha without clinging to appearances is the true way to pay respect.

Koans are meant to be deeply contemplated and explored by practitioners as a way to spark profound insight. The koan of Danxia Burning the Buddha teaches us that seeking truth through external appearances only leads to greater attachment.

In the Chan tradition, there are koans like “Yunmen’s Cake” and “Zhaozhou’s Tea,” which are meant to help practitioners break free from deluded thinking and the habit of making mental distinctions. When someone asks about the Dharma, if it’s explained with words and concepts, those words become fixed ideas that the speaker or listener may cling to. But if nothing is said, then nothing is revealed. If one says “there is,” the mind attaches to existence; if one says “there is not,” it clings to non-existence. Chan teaches us not to fall into these dualistic distinctions of “being” and “non-being.”

With a mind free of clinging in all situations, one comes to see that “the ordinary mind is the way”: drinking tea, eating food, carrying water, chopping wood, entertaining guests—everything is a part of Chan practice. As long as a practitioner applies effort from a state of non-attachment, realization will come naturally, like water flowing into a channel. There’s no need to force it or chase after it.

To “see the true nature of the mind” means to let go of all attachments in the heart, and directly witness and awaken to one’s true mind.